Open and explore more in ChatGPT

Imagine you were given $13,285,226 to invent something.

Better yet, you have sixty-two thousand customers ready to go. Evangelists. Early adopters.

So you take something good and make it better. You bolt on a USB charger. Add a waterproof Bluetooth speaker. Toss in an LED light. You take the idea of a Swiss Army Knife, smash it together with a cooler, and go nuts.

That was Ryan Grepper, the inventor of the Coolest Cooler.

In his words, “the COOLEST is a portable party disguised as a cooler, bringing blended drinks, music, and fun to any outdoor occasion.” Beyond the basics, his list of features was a grab-bag of tailgate dreams: A blender. A speaker. A phone charger. LED lights. A gear tie-down. Cutting board. Utensil storage. A bottle opener. All rolling on extra-wide tires.

It made a huge splash on Kickstarter and quickly became a huge failure.

Why do companies so often pursue innovation, and so often flunk?

I’ll bet innovation is somewhere in your list of priorities. Near the top of one of your strategy decks. Front and center at the next offsite. Snuggled between AI and customer obsession.

But while most large companies pin their hopes on innovation, only a handful of senior execs are satisfied with their performance, according to McKinsey.

So what’s going on?

While the well-worn Edison quote of “One percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration” is probably true, innovation doesn’t come from a single spark.

There is no Eureka! moment.

Innovation comes from running multiple engines concurrently. Each one pushing in a different direction, with a different mindset.

Innovative companies know this. These engines explain why innovative companies work—and where innovation fails.

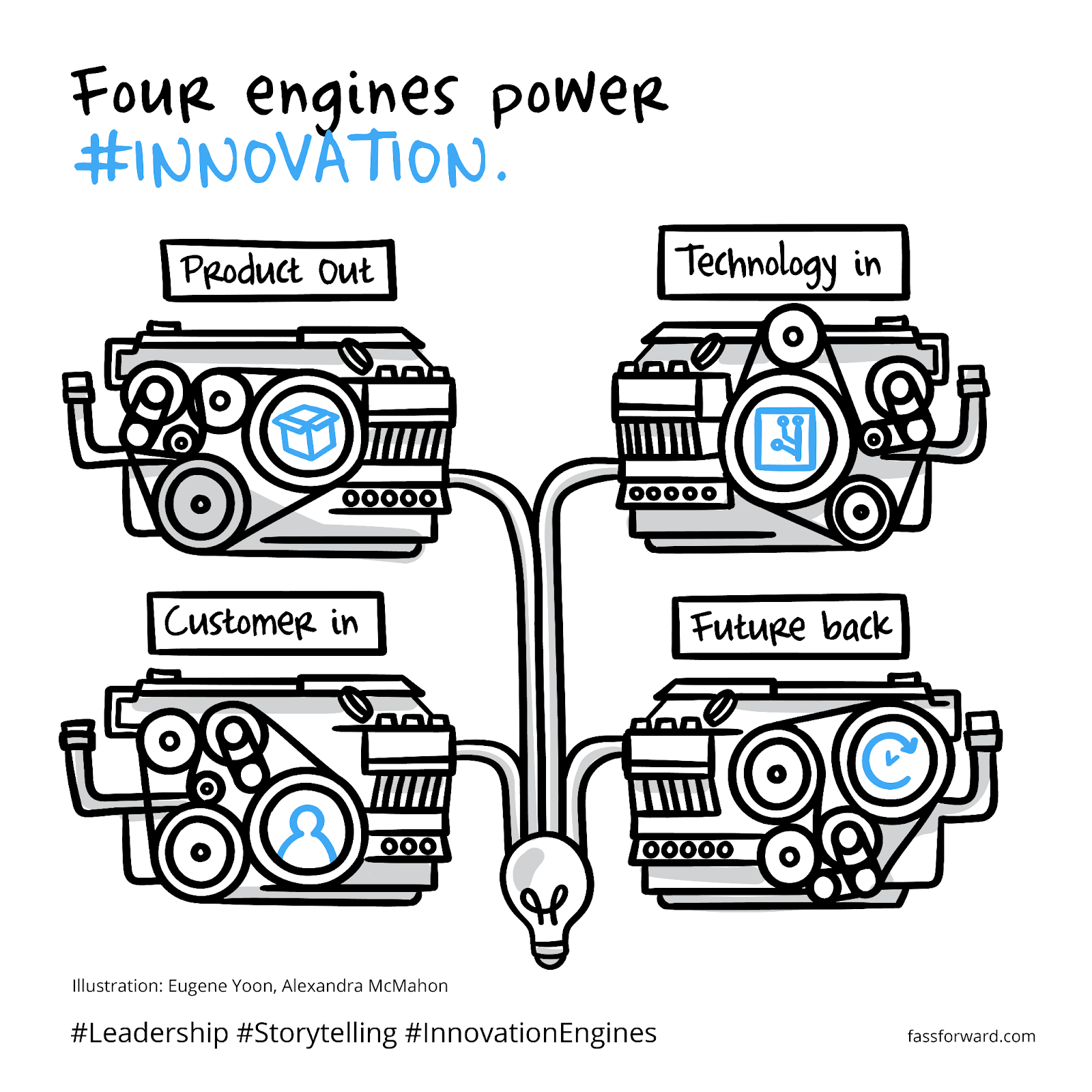

Four engines power innovation:

Product out is about making the thing better.

Technology in borrows new tools, models, or technologies.

Customer in designs around customers' needs, not wants.

Future back bets on what’s next.

The out, in, and back are essential. They imply that each engine runs on a different track—a different vector. Each is a different point of view. Each requires a different mindset.

Product out is about engineering and iteration.

Technology in is about scanning and remixing.

Customer in requires empathy and observation.

Future back calls for vision and imagination.

Individuals, teams, and leaders are wired for one or two of those.

This is functional fixedness; if I have a hammer, everything is a nail. It’s the trap that makes us see a screwdriver and think it can only turn screws. We can’t imagine it as a lever, a wedge, or a weapon.

In organizations, this shows up as a disciplinary bias. Engineering teams run on Product out. Design teams and marketing live in Customer in. Technology naturally sees every problem as Technology in. Strategists and the senior team may bet on Future back.

To innovate, individuals and organizations have to be open to unlearning—ready to switch on, run, and align all of these engines.

Making the thing better.

This is the engine of iteration, refinement, and improvement. It’s feature-rich, tinkering, and fettling. It’s engineering-led, execution heavy, and often lives close to core operations.

This mindset comes with fixed phrases:

“Can we add a new feature?”

“How do we ship faster?”

“Let’s improve what we did last time.”

Real-world examples abound.

Think every iPhone generation from 1 to 15. Apple refines the camera, ups the display quality, and revs up the chip speed. Polish. Gain in increments. Each improvement drives share, sales, and margin, but the iPhone 15 isn’t fundamentally different from the first iPhone.

The same idea, kaizen’ed.

Most businesses live here.

Product out is the bread and butter of product development. It’s familiar. Comfortable. Budgeted. But Product out alone won’t give you breakthrough innovation. At best, it keeps you in the game. At worst, it’s a slow slide to irrelevance.

Overinvestment in product tweaks adds complexity, not value. It might be great engineering, but a poor market fit.

Borrowing new tools, models, or technologies.

This is the engine of adoption, adaptation, and remixing. It’s curiosity-driven. Outside-in. Often experimental.

It looks at what’s possible elsewhere—and asks, “What if we used it here?”

This mindset comes with fixed phrases:

“Can we plug this in?”

“What else could this do?”

“Who’s already solved a problem like this?”

Think touchscreen GPS. TomTom took map data, embedded systems, and touchscreen tech—none of it new—and combined it into a breakthrough consumer device. That’s invention as recombination.

The innovation wasn’t in the components—it was in the remix.

Technology in is scanning the horizon—and the competition—for something new to add to the mix. It’s the Estée Lauder chemist who goes to paint industry conferences to learn about advances in polymer science—and comes back ready to reinvent makeup.

It’s not just pure technology; it’s business model crossover; an Amazon team thinking about Airline loyalty programs, adding a pinch of Costco magic, and dreaming up Amazon Prime.

But Technology in alone is risky. Just because you can build it, doesn’t mean you should. Google Glass, anyone? Meta’s Smart Glasses? Segway?

That’s shiny object syndrome. Tool first thinking without a user point of view, a market that wants it, or an ecosystem ready for it.

Designing around needs, not wants.

Listening for the wish. This is the engine of insight, empathy, and behavior. It’s where design thinking sits. Understanding not just what customers say they want—but what they’re actually trying to do.

This stands product on its head.

Not, “here’s what we made.” But instead, “here’s what they need.”

This mindset comes with fixed phrases:

“Why are they doing it that way?”

“What’s the workaround here?”

“What’s the job to be done?”

Notion is a textbook example of innovation powered by the Customer in engine. They noticed people cobbling together ‘Frankenstacks’ of productivity tools. Notes in Evernote. Docs in Google. Tasks in Todoist. Then cobbling it together with Zapier and Slack. Notion built a product around how humans actually work, and innovated in the seams between software categories.

Airbnb, Venmo, and others understand that Customer in requires fieldwork: Ethnographic research. Usage data. Heat maps. Shadowing. User research before you build the product, not after, to validate all your hard work.

But Customer in alone isn’t enough.

Overindexing on the voice of the customer can lead to flops like New Coke and Heinz EZ Squirt ketchup. Both were short-lived consumer products where well-intentioned innovators only asked some of the right questions:

“Do you prefer your Coke a little sweeter?”

“Wouldn’t purple ketchup be fun?”

They got the answers they were looking for, not the behavior they were betting on.

What’s next? That’s a hard question to answer.

This is the engine of vision, foresight, and framing.

It’s strategy-driven. Narrative-heavy. Often uncomfortable. Scenario planning and long-bet thinking live here.

It starts with taking educated guesses at where the world is going—and asks, “How do we lead there?”

This mindset comes with its own fixed phrases:

“What’s the future we want to shape?”

“What will matter five years from now?”

“What’s the bold bet?”

Think of Space—building not just for the next launch, but to make life multiplanetary. Or Netflix—reading the bandwidth and pivoting to streaming while competitors clung to DVDs.

Future back is rarely obvious, except in hindsight. For every AWS and cloud, there is a Magic Leap and Second Life. It takes conviction, capital, and a tolerance for being early.

The engines run together and support each other.

One builds from the product.

One borrows from technology.

One listens to the customer.

One bets on the future.

Most teams run on one engine. Maybe two, if they’re lucky.

But the best innovations run on all four. They run in sync because the culture allows it, and the innovation story aligns with it.

OpenAI doesn’t just ship better models. That’s Product out.

It pulls in breakthroughs from transformer architectures and alignment research. That’s Technology in.

It shapes around human behavior—chat as the interface, natural language as the operating system. That’s Customer in.

And it’s betting big on what’s next. AGI. Safety. Multimodal reasoning. That’s Future back.

A culture that moves fast, tolerates ambiguity, and obsesses over mission.

And a story that frames the stakes—not just what they're building, but why it matters.

Culture makes it possible. Story makes it stick.

Open and explore more in ChatGPT!

Open and explore more in ChatGPT

Leadership isn’t about the title you hold. It’s about how you show up. How you think, act, and shape the world around you.

And this takes practice.

Leadership is a practice. A maturity you must build—and rebuild—over time. It doesn’t grow in a straight line. It loops.

Under pressure, we slide. At every level, we face new traps. But if we pay attention, if we’re curious, if we learn, we can move forward.

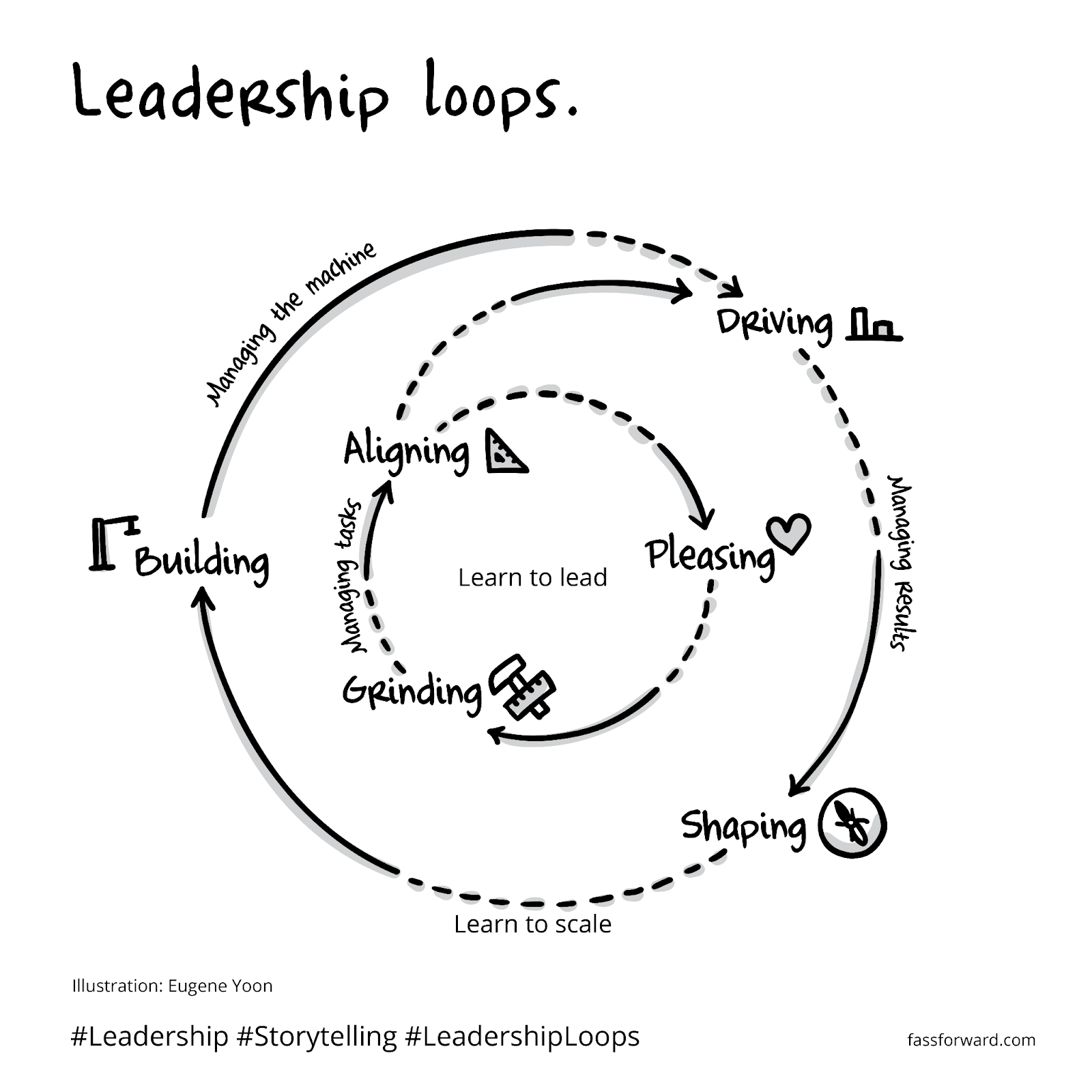

There are two loops.

The inner loop is where you learn to lead. It’s focused inward and downward, on your team. Team 2.

The outer loop is where you learn to scale. It’s focused upward and across, on your peers and the organization. Team 1.

Learning to lead. This is where it starts: managing your team. Your energy is downward. You focus on how your team feels, how much they get done, and how their work lines up to a bigger goal.

The ultimate lesson is separation. You manage work, and you lead people.

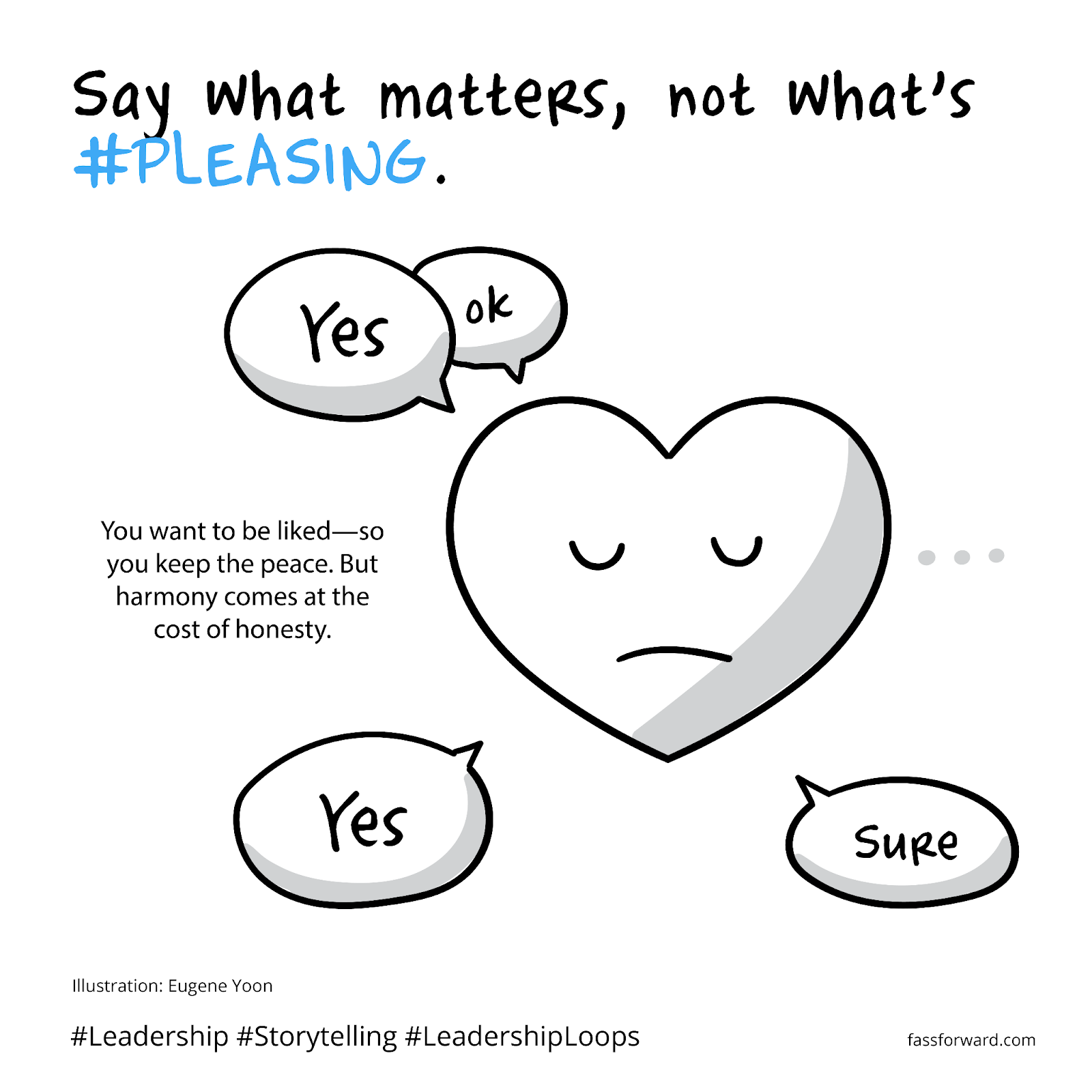

You want to be liked. You avoid conflict. Harmony conquers candor.

This is normal. You focus more on Team 2—your direct reports—than Team 1, your peers. You want a positive culture. A good place to work. But sometimes, that means avoiding tension instead of facing it.

You smooth things over. You say yes too often.

The trap: You avoid tough conversations. You mistake approval for progress.

The shift: Anchor to purpose, not popularity. Candor builds trust.

You get s**** done. Lists matter. Speed beats strategy.

You want to prove you can handle it—that you're reliable. That you and your team deliver. So you stay close to Team 2—clearing to-dos, jumping on problems, putting out fires. But sometimes, speed comes at the cost of direction. You don’t step back. You don’t set priorities. You don’t teach.

You mistake motion for momentum.

The trap: You become the fixer. You work harder instead of smarter.

The shift: Step back. Move from doing the work to directing the work. Teach.

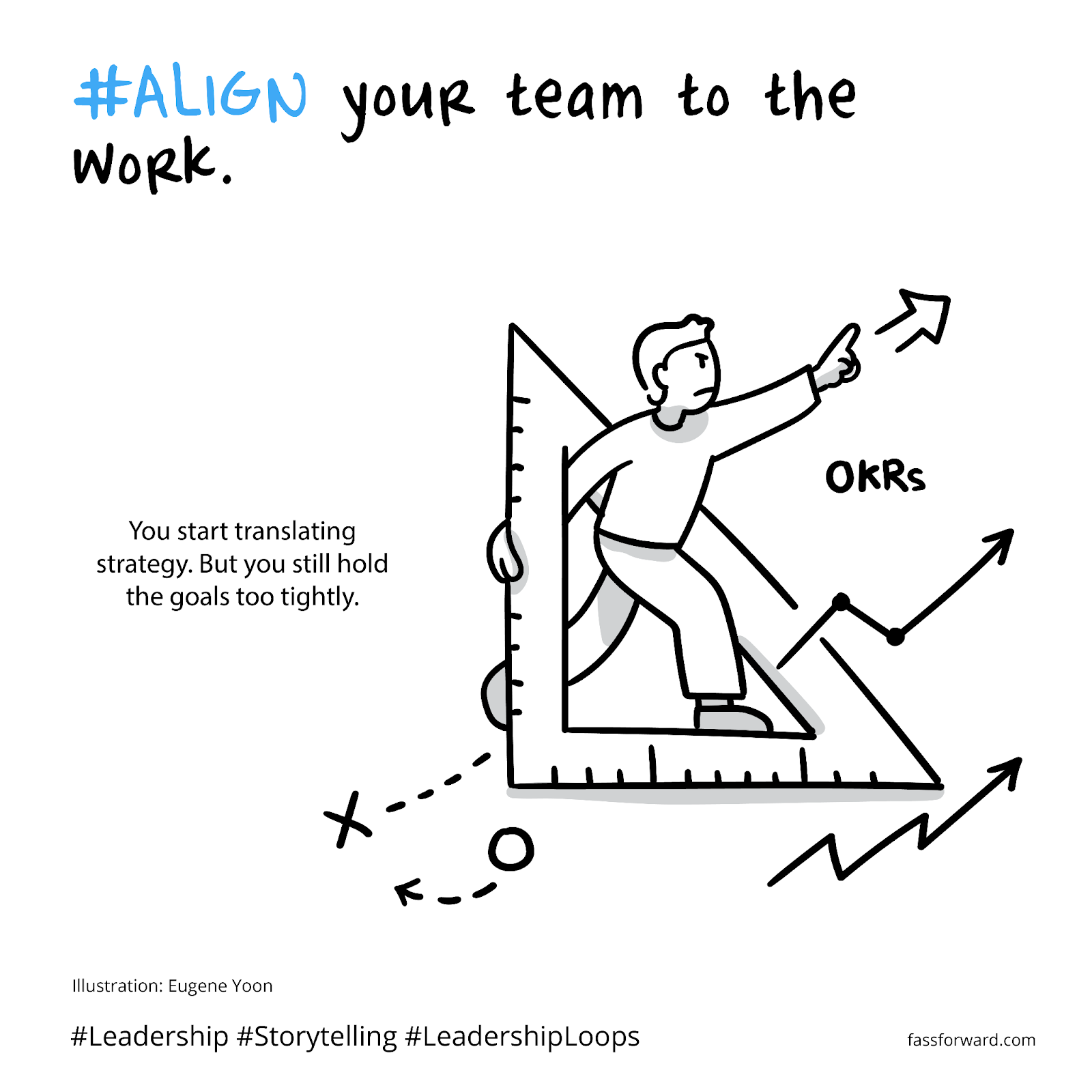

You start pointing the way. Translating strategy. You prioritize.

You want your team to see the bigger picture—and their part in it. So you lift your head. You look sideways and up. You spend more time with Team 1. You connect dots. You explain the “why.” You introduce OKRs.

But the vision still lives in your head. The goals are still yours to chase.

You haven’t let go.

The trap: You over-own. You stay at the center of everything.

The shift: Let go. Delegate. Use OKRs to invite shared ownership.

This is expansive leadership. You have separated managing work from leading people. Now, you lead with your peers. Your energy is outward.

You connect dots. You set the tone. You push the work forward.

You shape culture. You translate strategy. You build systems.

The ultimate lesson is scale. You stop being the hero. You become the builder. You don’t just lead teams—you create the conditions for teams to lead themselves.

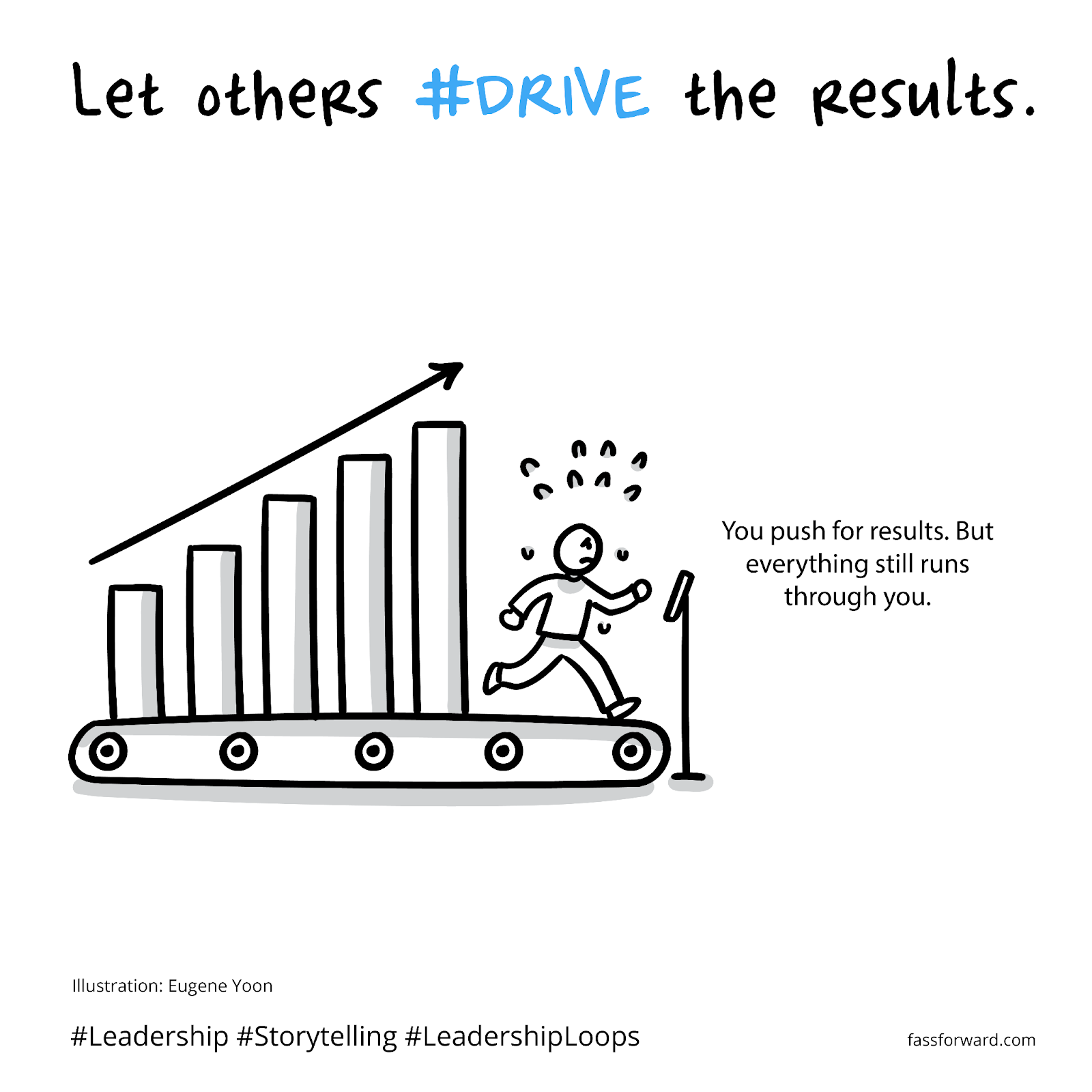

You raise the bar. You push for productivity. You prioritize results.

You’ve earned a seat at the table—and now, you want to deliver. You stay connected to Team 2, but your focus shifts to Team 1. You lead across. You set the pace. You measure what matters.

But performance runs through you. Every major decision. Every approval. Every next step.

You’re still cranking the engine.

The trap: You become the bottleneck. Everything depends on you.

The shift: Step aside. Shift from force to flow. Embed ownership in the team.

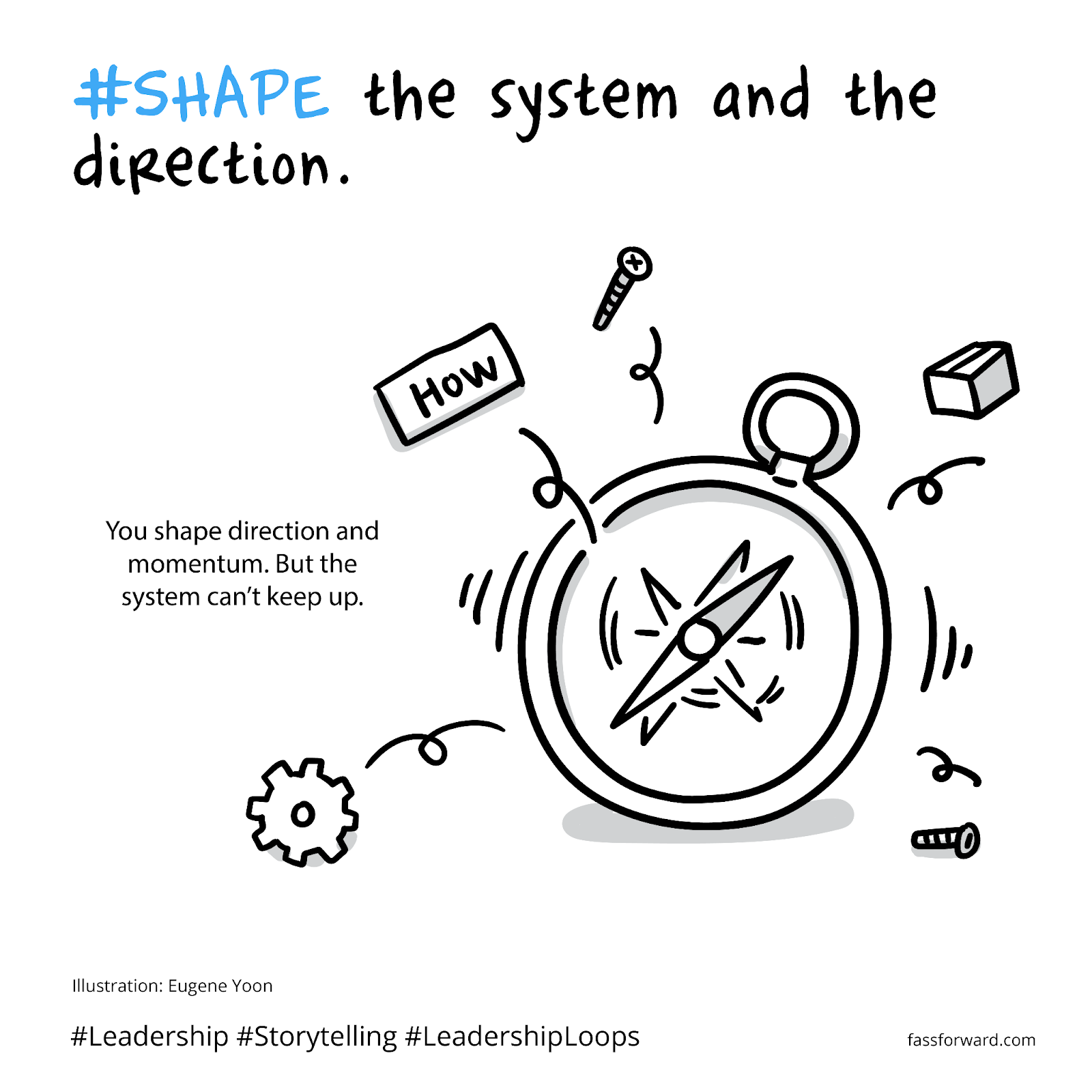

You’re connecting dots. You’re setting the tone. You’re pushing the work forward.

You want clarity across the board. You want teams aligned and momentum building. So you shape direction. You clarify what matters. You drive shared priorities.

But ambition outpaces execution. The vision is clear—but delivery lags behind. You’re shaping the what and the why—but the how isn’t holding.

You haven’t built the system yet.

The trap: You lead ahead of the system. Strategy breaks from execution.

The shift: Slow down to scale up. Shape the system while you shape direction.

Zoom out. Zoom in. Think long-term and short-term. Build for scale.

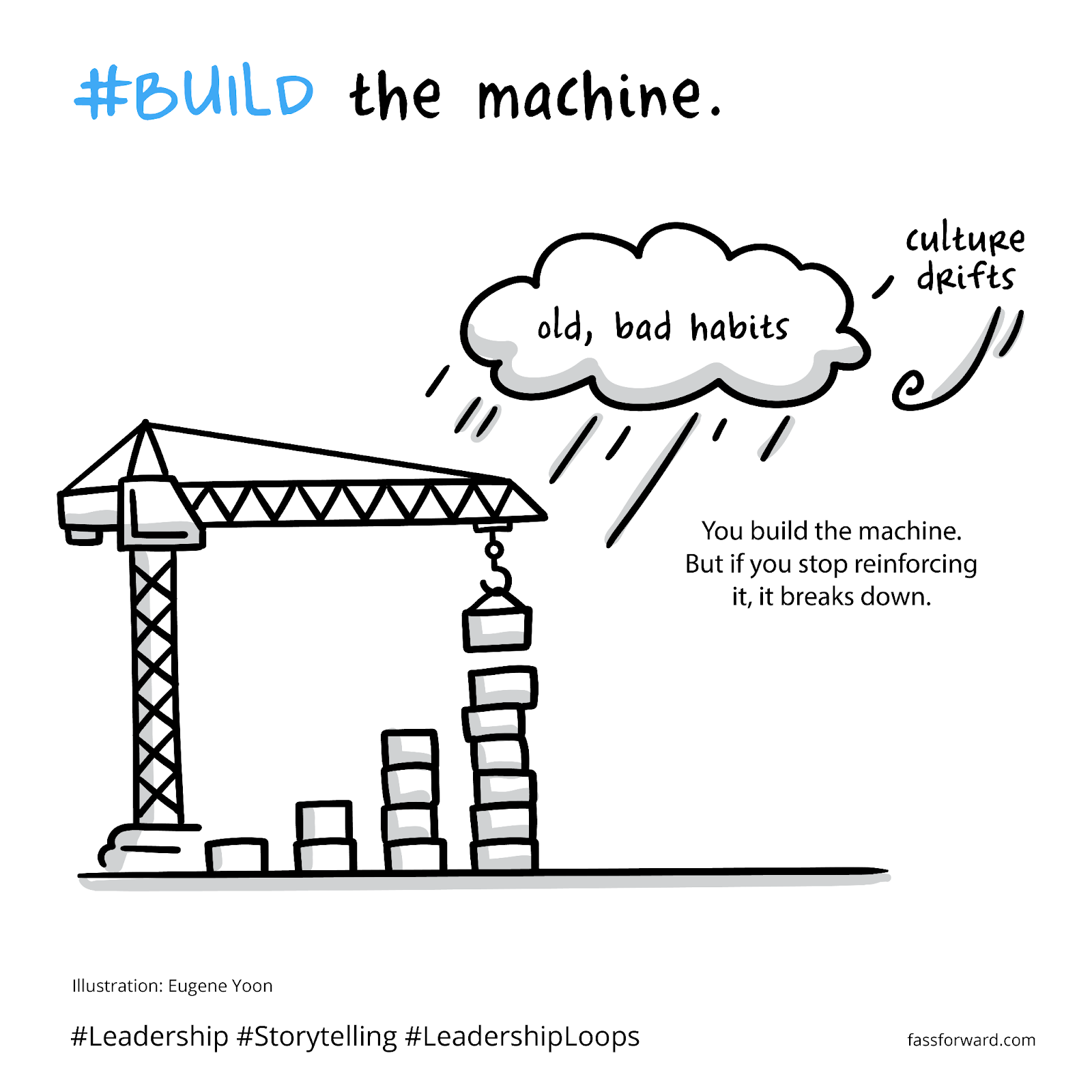

You design systems. You shape culture. You grow other leaders. You build the machine.

You want results that last—beyond you, without you. So you simplify. You codify. You create patterns. You invest in rituals, feedback loops, and operating models.

The danger isn’t distance. It’s drift. The machine starts to slip. Systems ossify. Culture drifts. People slide back into old—bad—habits. And if you’re not careful, you do too.

The trap: You let go too much. You slip back instead of scaling forward.

The shift: Stay close enough. Keep building. Reinforce what matters—until the system runs strong without you.

Leadership loops. You don’t finish them—you cycle through them.

You grow. You slip. You rebuild.

Ask yourself:

Where are you now?

Which loop are you in?

And what’s your next move?

We think a lot about teams.

How to lift them. How they drive performance in the business. How they shape culture. How they lead change, build with a product mindset, and translate strategy into action.

And it matters—McKinsey found that in critical roles, top performers don’t just outperform—they multiply. Up to 8x more productive than their peers.

So it’s worth asking, now and then, who’s on the team?

And more to the point—who shouldn’t be?

Meet the anti-team.

This roster of villains will do everything to slow you down. Left unchecked, they will put a wrench in the machine. They jam signals and erode trust. They’re a jargon-producing menace who make the simple complicated, and the straightforward complex.

You’ve met them before. You might be hiring them. You might even be creating them.

In descending order of dysfunction, they are:

#1. Mirrors.

#2. Puppets.

#3. Ghosts.

#4. Anchors.

#5. Spotlighters.

#6. Saboteurs.

You like them. Why wouldn’t you? They are a reflection of you. They think like you, act like you, echo your opinions. They nod along and rarely push back.

But that’s the problem. Mirrors don’t add—they reflect. And each reflection is a paler copy of the original. You get agreement without insight. Alignment without tension. Safe thinking. No friction.

Distortion disguised as agreement.

You’ll spot them by how quickly they agree, how often they reuse your words, and how rarely they bring something new to the table.

Mirrors are usually skilled and capable. Somewhere along the way, when status or certainty felt threatened, they traded originality for safety.

To shift them, invite dissent.

Demand candor. It doesn’t take confrontation—it takes a different task. Push them by giving them a safe way to push back. Put them in the role of a healthy skeptic. Have them lead a pre-mortem—a review of a project where they map out everything that could go wrong, before it does.

You want an anti-mirror: a challenger.

Someone who makes your ideas sharper, not softer.

They’re helpful. Reliable. They never push back. Never raise a hand. Never ask, “Why are we doing this?” They just nod, take notes, and wait for instructions. At first, that feels like a gift—someone who gets things done without hassle.

But puppets don’t think. They do. They’ve abdicated autonomy. You do the thinking—and the checking. You get execution without judgment. Transactions. Output without accountability.

The task gets done, but the point gets missed.

Watch what they don’t do. They ask, “Is this what you had in mind?” or wait for direction before making even small decisions. They’re always busy, but rarely out in front.

Puppets have skill. What they lack is will. At some point—possibly from you—they learned taking initiative meant risking blame. So they stopped.

To shift them, give them the problem, not the task. Ask for their take before sharing yours. Push them to make the first call—and most importantly, back them when they do.

You want an anti-puppet: an owner.

Someone who thinks before acting—and takes accountability for the outcome.

They were on the calendar. In the room. On the thread. But not really. They show up without showing up. There in body, but not in spirit. They’re silent in meetings. Absent in decisions. Invisible when work gets hard.

Ghosts don’t cause drama. They don’t stir conflict. They just... fade. You get presence without pull. Involvement without initiative. Login without lift.

They’re there, but not there.

You’ll notice them by their silence. Initials on a Zoom call. They don’t volunteer. They don’t raise blockers. And they don’t follow up. When the pressure’s on, they’re hard to find—and harder to count on.

Ghosts usually have the skill. They lack the will. That might look like laziness, but often it’s not. It’s overload. Or burnout. Or fear. When people feel their effort won’t matter—or won’t be safe—they pull back.

To move them, motivate them. Reconnect their work to what matters—to them. Ask what’s getting in their way. Make it safe to speak up, and make it count when they do.

You want an anti-ghost: a driver.

Someone who brings energy, not just attendance.

They might not mean to slow you down, but they do.

They question everything. Claim change fatigue. Rerun history with “why not...” and “what happened when.” They challenge every idea. Flag every risk. They ask for more data, more detail, and more time.

At first, it sounds like prudence. But anchors don’t let up. A decision made is a decision to reopen. Caution leeches away contribution. Feedback that sounds smart, but keeps you stuck.

Anchors resist change, hoping, “This too shall pass.”

You won’t hear a direct “no.” You’ll hear “let’s revisit,” “have we considered,” or “I’m not sure we’re ready.” Resistance, disguised as thoughtfulness.

Anchors often have both will and skill. They’re just not aligned with your agenda. They lack belief in the plan, in its pace, or the payoff. One foot in the past, unable to see the future.

To move them, engage them early. Invite them to shape the solution. Have them develop story 1 (the journey) and story 2 (the destination). Help them see themselves in the picture they’re resisting.

You want an anti-anchor: a catalyst.

Someone who helps you move—not holds you back.

They love the stage. The moment. The mic drop.

They lean in when the spotlight’s on, and step back when the real push begins. They show up big in meetings, pitch decks, and executive briefings. They speak in sound bites. Share wins, not worries.

When the work gets messy—when the team needs grit—they’re hard to find. Persistence isn’t their strong suit.

Spotlighters chase recognition, not results.

See how fast they jump in, and how fast they fade. They lead the kick-off, but miss the check-in, already chasing the next big thing. They celebrate outcomes they didn’t help drive. First to post, last to push.

Spotlighters have skill and will, but it’s misdirected. They invest where the recognition is, not where the real work happens.

Sometimes it’s ambition. Sometimes insecurity. Often, it’s a learned behavior in environments that reward heroes, not hard work.

To move them, shift what you celebrate. Glorify effort, contribution, and perseverance—the small steps, not just the big gains. Shine a light on follow-through and follow-up. Track ownership, not airtime.

You want an anti-spotlighter: a steward.

Someone who stays with it, not just when the lights are on.

They don’t just block the work. They break the machine.

Saboteurs were French factory workers who tossed their wooden shoes—sabots—into machines to grind them to a halt. Now they’re on your team. Whispering doubt. Stirring resentment. Building friction.

Sometimes it's subtle: passive resistance, loaded questions, side comments, and backchannels.

They undermine trust and corrode culture.

You’ll feel it before you see it. People pull back. Meetings get tense. Pocket vetoes multiply.

Saboteurs often have both will and skill. They lack alignment. They’re smart, experienced, and working against you. Sometimes it’s political. Sometimes it’s personal. Often, it’s a response to feeling sidelined, unrecognized, or a loss of power.

To move them, surface the behavior. Name it—clearly and calmly. Set clear expectations and guardrails. Don’t feed into the behavior by tiptoeing around it. And if nothing changes, you may need to make a tough call.

You want an anti-saboteur: a force multiplier.

Someone who builds trust, fuels momentum, and makes everyone around them better.

The best teams don’t just happen.

They’re shaped by who you bet on, who you build up, and who you stop carrying

Everyone’s chasing the next big thing. A new app. A better mousetrap. A new AI something-a-jig.

But novelty alone isn’t the answer.

Innovation is not new.

For a product-leading company, it’s not a new product—it’s a better way of delivering value that customers care about.

For a customer-intimate company, it’s not a new feature—it’s a deeper relationship that creates opportunity.

For an operationally excellent company, it’s not a new process—it’s a better outcome at scale.

The pressure to innovate never stops.

Customers expect it. Competitors chase it. Change demands it.

But not all that is new moves the needle.

Innovation, then, follows a simple formula:

Without Novelty, innovation is ho-hum. Lacking Value, you have a gimmick. Deduct Impact, and you have a missed opportunity.

Novelty is a new product, feature, or process. Value is what customers care about: the resolution to their problem, a job to be done. Impact changes a behavior at scale. The product gives its end user a better version of themselves.

Value comes from making it—the job to be done—cheaper, faster, easier, or smarter.

Impact is the differential. The difference between the old way and the new way. The difference between the old me, and the new version of me.

Look at any innovation—chopping and bagging a lettuce (Fresh Express), putting a million songs in your pocket (Spotify), turning taxis into apps (Uber), from renting to streaming (Netflix), going to the store to pressing “Buy now” (Amazon).

You see patterns.

Those patterns—those truths—can guide your innovation journey, whether you are rethinking a product, reinventing a process, or redesigning a service. They are:

#1. Innovation is a remix.

#2. Innovation lives in the seams.

#3. Innovation loops and learns.

#4. Innovation dies without execution.

#5. Innovation requires unlearning.

#6. Innovation lives in a system.

When Steve Jobs launched the iPhone in 2007. He told a story of three technologies fused together: A wide-screen iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone, and a breakthrough internet communications device. Three devices, fused together.

Jobs’ genius was to remix. The Mac took from his college fascination with calligraphy. Pixar blended storytelling and computer graphics to reinvent animation. NeXT and later the iMac reimagined software and hardware design—merging beauty and function.

Innovation doesn’t come from nowhere.

It’s the recombination of existing ideas, tech, or models—reframed in a new context. Great innovators borrow, blend, and bend what already exists to unlock new value.

Think DJ, not diva.

Write → Save → Attach → Email → Edit → Repeat.

Throw in a couple of blue screens, and you have collaboration circa 2010. Teamwork by inbox. Collaboration by version control.

Then Google changed the game. They bought Writely, an online text editor. And Docverse, which lets people co-edit traditional office files.

The seam: collaboration. The result: a living document.

Write → Edit → [Collaborate]

One doc. One team. One shared space.

Innovation crosses boundaries—product, process, service, business model, experience.

Real innovation rarely stays in its lane. And when it hops categories, it changes the game.

If it doesn’t challenge a boundary, it’s just an upgrade.

Humans like straight lines and good stories.

Here’s one consultants tell: NASA spent millions of dollars developing a pen to write in space, while the Russians used a pencil.

Codswallop.

Pencils break. Tips float. Graphite dust is flammable and conductive—not ideal in a pressurized capsule filled with electronics and oxygen.

The real story: Paul Fisher, a private inventor, spent his own money to develop the Fisher Space Pen, filled with a pressurized ink cartridge that could write upside down, underwater, and in zero gravity.

NASA tested it, then bought it. So did the Russians.

Both agencies still use it today.

Successful innovation moves through stages:

Idea → Concept → Prototype → Development → Production → Adoption.

Each stage is a gate. And at every gate, it can fail—and teach you something.

Innovation isn’t smooth. It’s not a straight line. It’s a loop—of learning, adjusting, and adapting. The best innovators constantly circle back. They iterate. They test again.

And get smarter with every pass.

Ideas are ten a penny. They’re important, just not that important.

Execution matters. Idea to sketch. PowerPoint to prototype. Prototype to production. Production to payoff.

Pinocchio wasn’t real because he was carved from wood.

He became real through struggle: every setback taught him something. That’s the path to execution. The devil is in the details.

James Dyson had an idea after his vacuum clogged. He worked the problem. 5,127 prototypes and five years later, he launched a product that changed the industry.

Ideas are cheap—especially now, with AI. What is not? The persistence that brings an idea to life. Shipping is hard. Testing, building, scaling, and surviving resistance—is the sweaty part.

It’s not the spark. It’s the follow-through.

Everything is obvious once you know the answer.

But if pre-cut, bagged lettuce is so obvious, why didn’t anyone do it sooner?

Why did it take Amazon so long to invent 1-click ordering?

Technically, they could have launched it in 1996. They had user accounts. They stored credit card and shipping info. They ran their own checkout pipeline.

So why wait three years?

Because the dominant mental model was retail brain—copying the physical store into a digital world. Shopping carts, multi-step checkouts, and a final confirmation.

The logic of bricks and mortar, ported to pixels.

Three years isn’t a long time for the obvious to emerge. Try 112 years.

Martin Eberhard drove his first roadster in 2006, three years after founding Tesla. That’s a blink compared to the Electrobat, the first commercially viable working electric car, in 1894

Why did it take so long?

Because for 100 years, we believed gasoline was the future. That range, speed, and power only came from combustion. Infrastructure followed belief. And belief is hard to unlearn.

The biggest barrier to innovation isn’t imagination—it’s expertise.

The logic that made you successful is blocking what’s next. To invent, you must first unlearn.

You have to let go of what you know to see what could be.

No idea wins in a vacuum.

In The Wide Lens, Ron Adner shows why some of the best innovations fall flat. Not for lack of imagination—but because the system wasn’t ready.

Adner tells the story of Philips’ CD-i—a 1990s multimedia platform that could play music, video, games, and more. A product ahead of its time.

But it lacked content. Retailers didn’t know how to sell it. Consumers didn’t know what it was for. It flopped. Not because of the product, but because of the system.

When Apple launched the iPod, it launched into an ecosystem. Music rights, handled by iTunes. USB 2.0 for faster syncing. An army of early adopters using Napster, Kazaa, and LimeWire.

The timing was right, the partners were ready, and the customers were primed.

Product-market fit means you are solving a problem people care about. Ecosystem fit means the world is ready for your answer.

Customers, partners, timing, and readiness all matter. Ecosystem fit is as critical as product fit.

A brilliant idea at the wrong time is still a failure.

"Al won't take your job, it's somebody using Al that will take your job."

I believe this comment by Economist Richard Baldwin at the 2023 World Economic Forum's Growth Summit sums it up best. Al is already transforming leadership coaching. According to a May 2024 data from Similarweb, ChatGPT attracts 260.2 million visitors each month. If you are not using Al yet, you can feel confident that your competitors are.

A Powerful Partner

Al is a game changer for the coaching industry.

One of the biggest advantages Al brings is a more rapid, data-driven approach to coaching.

Traditionally, coaching has relied on subjective feedback from peers or annual reviews. With Al, our coaches can synthesize vast amounts of data ranging from 360 feedback to results from our proprietary tools to their coaching calls in a fraction of the time they used to and with more accuracy. This also allows our coaches, who are on call for our clients, to... [Read more here]

You: I’m proud of the team. They’ve really stepped up.

Your boss: Yeah? How so?

You: They’re owning it. Helping each other. Calling out issues. Getting stuff done. It’s starting to feel like a real team.

(pause)

Your boss: Which team are you talking about?

You probably didn’t even hesitate before answering. And that’s the problem.

...

You may not realize it, but you are on at least two teams.

The team you lead—and the team you lead with.

Most of us don’t think that way. We default to calling the team we lead “my team.” We refer to the other one—our peer group—as “the senior team” or “the leadership team.”

Which, if we’re honest, we think of as our boss’s team.

Wrong.

Patrick Lencioni makes this clear in The Advantage.

“Leaders are not there simply to represent the departments that they lead and manage but rather to solve problems that stand in the way of achieving success for the whole organization.”

In most cases, the opposite is true.

“When members of a leadership team feel a stronger sense of commitment and loyalty to the team they lead than the one they’re a member of, then the team they’re a member of becomes like the U.S. Congress or the United Nations: it’s just a place where people come together to lobby for their constituents.”

It’s a simple but powerful idea.

Team 2 is the team you lead. Team 1 is the team you lead with.

Embracing that mindset is a cure.

A cure for siloed thinking, turf wars, misaligned priorities, slow decision making, bureaucracy, and swirl.

Siloed thinking is “my part works.”

It’s staying in your lane, hoarding information, and building up coordination debt—the hidden cost of not working across teams.

Turf wars are “that’s mine.”

When leaders defend their patch instead of solving for the whole. The political intrigue. The meeting after the meeting. Passive-aggressive infighting.

Misaligned priorities: “We’re not on the same page.”

Every team is pulling in a slightly different direction. One’s sprinting. One’s stalled. One is solving the wrong problem.

Slow decision making: “Let’s circle back.”

No one owns the call—or worse, everyone’s waiting on each other. More data is requested. Problems drift. Cans are kicked.

Bureaucracy or “check in with me first”

Process becomes a proxy for trust. Hierarchy matters. Rules trump relationships. Forms and formality prevails.

Swirl: “Haven’t we had this conversation before?”

Rework and rehashing. Stuff moves at a glacial pace. Ducks are lined up, the order is questioned, and the ducks line up again.

That shift—from leading your team to leading with a first team mindset—changes everything.

It pulls you out of silos and shortcuts toward enterprise success.

These six rules make it real.

#1. Lead with one face.

#2. Say the hard thing.

#3. Hold each other to the standard.

#4. Own the outcomes.

#5. Speak as one.

#6. Make it make sense.

Here’s what each rule looks like in the wild.

It’s easy to act differently between Team 1 and Team 2.

The power dynamics are different. You’re not the most senior person in the room anymore. The stakes are higher. The audience is tougher. Someone has a bigger box than you on the org chart.

That creates pressure: to posture, to protect, to play it safe.

But here’s the thing: consistency builds trust.

People notice the difference when you’re open with your team but guarded with your peers. When you micromanage one way but defer in another. When you show empathy down but act defensively across.

Don’t wear two faces.

Authenticity isn’t a performance; it's a pattern. And people are watching.

You avoid conflict because you’re nice.

You’ve learned the hard way. Say the wrong thing: to a peer, to a boss, and it bites you. So you hedge. You soften. You caveat. You wait for someone else to go first.

But here’s the thing: Silence doesn’t keep the peace, it keeps the problem.

Team 1 isn’t about being nice; it’s about being clear. Candid. It’s what Lencioni calls “mining for conflict.” Actively looking for the tough conversations that most teams bury. Because when problems stay hidden, so does progress.

That means naming the issue. Surfacing the tension. Challenging the thinking—early, openly, and in the room.

You don’t have to be rude, but you have to be real. Deliver feedback in the moment, not after the fact.

Team 1 embraces candor during the conversation.

This is a key component of operational excellence—setting standards, then raising them.

It’s hard to set a standard. Harder still to live up to it. Hardest of all? Calling it out when someone doesn’t.

But that’s the job.

Accountability isn’t just vertical.

If someone’s off track, say it.

If something’s slipping, step in.

Feedback—sharing concerns as unmet needs, and asking team members to step up—should be the norm on Team 1 and Team 2.

Holding each other accountable to agree on standards, especially when no-one else does. Especially when it’s uncomfortable.

Especially when no one else is saying it.

True team 1 thinking is about creating outcomes.

Not just for your function—but for the business. Team 1 leaders walk out aligned—even if they walk in disagreeing.

It’s stepping outside the hierarchy. Sharing in enterprise success, not creating silos and protecting turf. This gets easier when outcomes are discussed, agreed, and shared.

Team 1 means shared goals. Shared accountability. One scoreboard. One outcome.

You can still advocate for your team. You should. But you also own the tradeoffs. The compromises. The messy middle.

This is where many leaders slip. They nod in the room—then shift the story afterward.

“It wasn’t my call.”

“They decided.”

“We’ll see how it plays out.”

That’s managerial ventriloquism. You become the mouthpiece for a decision you don’t own. And your Team 2 hears that.

Team 1 leaders speak with one voice.

They walk out aligned. Not to carry on the conversation in the corridor, but to carry the message with clarity and conviction.

To own the decision.

Decisions made in Team 1 don’t matter if they don’t land in Team 2.

It’s easy to repeat the “what.” Much harder to explain the “why.”

But that’s the job—translation, not transmission.

Your team doesn’t need cryptic slides or a word-for-word recap. They need message discipline. Clarity. Context. Simplicity. Better yet—radical simplicity.

If it’s not clear enough to remember, it’s not clear enough to act on.

If the message changes by the time it hits the front line, it’s not a cascade—it’s a game of telephone.

Making it make sense isn't just about what you—or they—say. It’s what they remember. What they repeat. What they act on.

So: which team are you showing up for?

Unlearning isn’t forgetting; it’s clearing old habits to make room for smarter ones.

Fifty years ago, Alvin Toffler made an unnerving prediction. “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

Add AI to the equation. A seismic upheaval in how we work is changing how we think. Call it (Toffler) x 10.

Calculators dulled our mental math. GPS eroded our sense of direction. Spellcheck weakened our spelling.

Now, AI summarizes documents we don’t want to read, writes emails we don’t want to write, and finds answers we don’t want to search for.

Outsourcing our thinking dulls the mind. If we let it.

As AI takes up the routine, it leaves us standing with Toffler’s challenge: learning, unlearning, and relearning.

Or at least, we were. That’s the story I am sticking to.

In 1968, NASA commissioned a study to find highly creative engineers and scientists. Researchers George Land and Beth Jarman tested for what they called divergent thinking—the ability to generate multiple, novel solutions to a problem.

When NASA engineers took the test, only a small fraction hit the “creative genius” level. But when 5-year-olds took it, 98% did. According to Land, “non-creative behavior is learned.”

We don’t lack creativity. We’ve layered over it with habits that get in the way.

To reclaim our creative genius, we have to unlearn these habits.

And before we do that, we must burst through some barriers:

Functional fixedness, the blinkers that prevent us seeing possibilities. If we have a hammer, we see nails everywhere. It’s the false confidence that we already know best.

Stuck thinking where how we react to problems follows a familiar groove. It’s not just the comfort with the familiar; it's discomfort with new ways of thinking.

We cling to opinion over evidence. Data doesn’t move people if it flies in the face of deeply held beliefs. We stick with old, familiar ideas, even when the facts should move us on.

Emotional attachment looms large. Our past successes and pride shapes who we are. Which makes letting go hard.

A culture of fear. Where it isn’t safe to make mistakes, or ask dumb questions, or it’s frowned upon to pick at sacred cows. Where failure is punished (or even perceived as such), people stay frozen.

Blind spots abound. You may not be familiar with the Johari Window, but you live in one. There are things others see (the known unknowns) and that no one sees (the unknown unknowns). The trouble is, blind spots stay blind, unless we’re willing to listen, look harder, and rethink.

Unlearning is hard because our brains are built to repeat, not rethink. We have to break habits and overcome defaults: the pull of the familiar, the comfort of being right, and the instinct to protect what worked before.

Unlearning takes six moves:

#1. Spot what’s stuck.

#2. Loosen your grip.

#3. Dig before you discard.

#4. Shift the payoff.

#5. Replace the habit.

#6. Unlearn together.

You can’t fix what you can’t see.

Once we’ve built habits—automated behaviors and ways of thinking—we stop questioning them. They dissolve into the background.

Look for friction that’s no longer noticed: clunky processes, functional silos, outdated KPIs, and reports no-one reads any more. Pay attention to new team members and outsiders with different perspectives.

Ask yourself:

What am I doing because it used to work? And,

What assumptions no longer hold true?

At AWS, teams use “Working Backwards” documents—starting with the ideal customer outcome and tracing backward to find friction. If it doesn’t serve the user, it’s up for debate.

At Spotify, retrospectives are a habit—not just in product teams, but across functions. Spotting what’s stuck is built into how they work.

At Stripe, internal postmortems are used to surface friction—without blame. It’s a structured way to find what’s broken before it slows work again.

You can start unlearning now.

Ask the team, “What are we doing that no longer makes sense?”

Write it down. Look for patterns, then act on them.

Holding on is what’s holding you back.

It’s the monkey jar principle. A monkey reaches into a jar to grab a piece of fruit... but can’t pull its hand out while still holding it. The monkey stays trapped, not because it’s tied down—but because it won’t let go.

We do the same thing. We hold onto old routines because they once brought success and status. We protect them. Defend them. Wrap our identity in them. Even when they no longer serve us.

Look for signs of grip: resistance to change that’s a pit in your stomach. Defensiveness that tightens your jaw. Perfectionism covering up anxiety.

Ask yourself:

What am I afraid to let go of—and why?

What would I stop doing if I didn’t have to protect [this]?

At AWS, writing a future press release forces teams to let go of today’s assumptions and imagine the product from a world that doesn’t exist yet. It creates a safe distance from the present and space to let go.

Spotify uses lightweight launch checklists that emphasize learning over perfection. Teams are encouraged to ship early, with known gaps, as long as there's a feedback loop in place. The focus is on momentum, not getting it perfect the first time.

At Stripe, new hires are invited to question—and even rewrite—their onboarding docs, including those written by their managers. It sends a clear message: what worked before isn’t sacred. Letting go is part of learning.

Loosen your grip.

Ask your team: “What are we holding onto that helped us then, but hurts us now?”

Say it out loud and let go together.

Unlearning isn’t a conflagration. It’s an excavation.

We don’t need to burn everything down.

Some ways of working served us well. Some still do. The danger is in assuming all legacy is dead weight or that every new idea is better by default.

Unlearning means sorting the gold from the gravel. Finding what needs to change and what can stay the same.

Clean-sheetism is great. For brainstorming. But it can lead to big swings, total resets, and a tendency to kill before we understand. At some point, it is met with resistance, and teams will throw out the old playbook only to recreate it under a new name.

Ask yourself:

Which part of this actually worked?

What ‘soft systems’ (relationships, rituals, norms) should stay?

What would we keep if we were starting from scratch?

At AWS, before building anything new, teams start with a press release and FAQ—then dig into existing workflows, metrics, and habits that might conflict with that future state. It’s not about throwing everything out—it’s about aligning what already exists with what customers actually need.

Spotify teams run “Start / Stop / Keep” sessions in retrospectives—not everything old gets tossed. Some rituals evolve. Some are revived, if they still serve the team.

Stripe teams regularly audit internal tools and processes before replacing them. Engineers are expected to ask: “Is the pain here in the tool—or how we’re using it?” Often, it’s not a rebuild that’s needed, just a rethink.

Find what matters and toss the rest.

Before you change something, stop and ask: “What are we trying to fix — and do we understand it well enough to move on?”

Don’t discard. Dig.

Unlearning is unnatural. It feels like failure.

Letting go of what once worked can feel like admitting you were wrong. Setting aside a routine, a system, a process—even a mindset—feels like a betrayal of what made you successful in the first place.

That's why we cling to the past.

To change the context, change the reward—from old to new:

These signals are sticky. They tell people what’s really valued—and what’s not.

Ask yourself:

What are we actually rewarding?

What behavior gets recognition, but might be holding us back?

What would we reward in a company that celebrates speed, learning, and impact?

Amazon rewards teams for spotting flawed assumptions early, not just for what ships. Failure isn’t punished; false certainty is.

At Spotify, speed of learning matters more than polish. Leaders praise fast feedback loops and smart pivots—momentum beats mastery.

At Stripe, senior leaders make a point of sharing what they’ve changed their minds about. That signals unlearning as strength, not loss.

Reward differently.

Shine a light on someone who stopped doing something that no longer worked and made space for something better.

Change what you celebrate.

Stopping isn’t enough. You have to swap it for something better.

Unlearning leaves a gap. A vacuum. A pause between what you used to do and what you’ll do next.

If you don’t fill that gap, the old habit creeps back in. That’s how defaults survive—not because they’re strong, but because they’re familiar.

Old habits fade when they’re overwritten, not just erased. You introduce a new tool, but no new ritual. You reorganize, but the same decisions happen in the same rooms. You remove a process, but nothing takes its place, so people snap back to what they know.

Ask yourself:

What will we do instead?

Does the replacement make the new habit easier, faster, clearer than the old one?

Have we practiced the new pattern enough for it to stick?

Amazon replaced traditional planning cycles with PR/FAQ—a new rhythm that shifts focus from timelines to customer clarity.

When Spotify reshapes teams, they don’t just retire roles—they install lightweight rituals like standups, demos, and retros. Process is replaced with presence.

Stripe simplifies by replacing, not just removing. When they sunset a tool or process, they launch a better default: something faster, lighter, and easier to adopt.

Stop. Then start something better.

When you stop something, pair it with a new behavior, tool, or trigger. Every “no more of this” needs a “from now on, we do that.”

Don’t just delete—replace.

Unlearning needs air cover.

A signal that it’s safe to question. That letting go isn’t failure — it’s expected. That breaking old patterns is a team sport. It’s safer to go together than to go alone.

If you’re going it alone:

You raise a concern, and no one touches it.

You try something new—and get quietly corrected.

Everyone agrees in the meeting, then questions it after the fact.

That’s not a culture of learning or unlearning. It’s a culture of compliance.

Ask yourself:

Who’s modeling unlearning here?

Do we make it safe to challenge—or do we shut it down?

Do we have a shared language for change?

Amazon builds unlearning into its narrative culture. Teams write six-page memos to challenge assumptions, test logic, and expose outdated thinking. The goal isn’t agreement—it’s rigorous debate.

At Spotify, retros aren’t just for postmortems—they’re for letting go. Teams name the habits, processes, or mindsets that no longer fit, and decide—together—what to leave behind.

Stripe leaders model unlearning by naming what they’ve changed their minds about—in meetings, docs, and Q&As. Change isn’t whispered; it’s shared out loud.

Start unlearning together.

Add one question to your next team review:

“What should we unlearn?”

Roger Federer, considered by many the greatest tennis player of all time, only won 54% of the points he played.

Think about that. GOAT. 82% win rate. One hundred and three career titles. Twenty Grand Slams. But any given point? Little more than fifty-fifty.

Winning teams don’t focus on the win.

They focus on getting better.

In competition—golf, rugby, Formula One—the same holds true. They follow the same pattern. The same six rules:

#1. Winning is a lagging indicator.

#2. Greatness comes from marginal gains.

#3. Moments matter; some more than others.

#4. Failure becomes fuel.

#5. Practice. Deliberately.

#6. Loyalty to the mission.

These aren’t just rules, they’re a system. The system that made Federer great, the All Blacks legendary, and Mercedes dominant.

So, why, in business, do so many teams focus on the win?

Winning isn’t the goal, it’s the outcome.

An outcome built not by chasing the win, but chasing the work. The reps. The refinement. The relentless pursuit of better.

Here’s how it breaks down.

Federer, speaking at Dartmouth’s 2024 commencement, shared a surprising truth: he only won 54% of the points he played. Even at the pinnacle of tennis, he lost almost every other point. Perfection wasn’t the goal. The next point was.

The outcome depends on not dwelling on the past but focusing on the future with clarity and determination.

So too, in business. A “win” is measured in outcomes—quarterly profits, market share, successful products. But outcomes are the result of many things: preparation, adaptability, mindset, execution, and perseverance.

They aren’t something you can directly control.

You can’t decide to “win” any more than you can choose to “have a great quarter.” You can control the process that leads there.

You don't win by aiming at the scoreboard. You win by aiming at the work.

🤔 Ask yourself: Are you chasing outcomes—or building habits that make outcomes inevitable?

Elite teams don’t wait for breakthroughs. They engineer them. They obsess over fundamentals. The All Blacks rewatch their training footage in slow motion—not to admire their form, but to fix the tiniest flaws in their footwork.

A 1% gain may not seem like much. But stacked across systems, processes, and habits, it’s unstoppable.

Winning businesses don’t bet everything on a moonshot. They focus on small, systematic improvements—shorter handoffs, clearer priorities, tighter meetings, sharper decisions.

Marginal gains in performance, process, and culture compound over time. Relentless refinement disguised as overnight success.

You don’t find greatness. You build it—one small improvement at a time.

🤔 Ask yourself: Are you stacking small gains—or standing still, waiting for a breakthrough?

In F1, pit stops are pivotal. Monaco, 2021. Valtteri Bottas brought his Mercedes in for a tyre change. The right front mechanic stripped the nut, irreversibly jamming the wheel on the car. Bottas’ race ended—not on the track, but in the pit lane.

Great teams understand: it's not about winning every moment, but about executing flawlessly when the moment matters.

In business, most moments are recoverable. Some—key pitches, product launches, high-stakes negotiations—are not.

You can’t always predict when the critical moment comes. You can only prepare to execute when it does.

You don't rise to the occasion. You fall to your preparation.

🤔 Ask yourself: Are you practicing for the big moment, or hoping you’ll rise to it?

New Zealand’s All Blacks. An island nation that expects rugby dominance. But they were knocked out of the 2007 World Cup in the quarter-finals. Not just a loss—a national crisis. The team re-examined everything: leadership, coaching relationships, mental preparation, identity. They re-centered around humility, clarity, and culture.

Four years later, on home soil, they lifted the World Cup.

Setbacks don’t break great teams. They sharpen them. So too, in business. High-performing teams fail. And they use that failure. They turn missteps into mirrors. They fix weak systems, upgrade processes, and harden culture.

Failure becomes a catalyst for change.

The best teams don’t fear failure; they metabolize it.

🤔 Ask yourself: When failure hits, are you alibiing or adjusting?

Before Tiger Woods, there was Nick Faldo.

In the 1980s, the young English golfer had a stylish, swooping swing. But it was unreliable. In the heat of major contention, Faldo knew it would break down. He took the radical step to totally rebuild his game. Two years. Up to 800 balls a day in the Florida heat.

The method wasn’t to practice until he got it right. It was to practice until he couldn’t get it wrong.

Through deliberate practice, Faldo found precision. Six major championships. And a reputation as one of the most mentally tough and technically sound players in history.

Great teams—and great players—don’t just practice. They practice deliberately, every move dissected, every detail sharpened, all in pursuit of mastery. High-performing teams don’t wing it. They rehearse. They run drills. They practice under pressure before it matters.

Deliberate practice isn’t doing the work once. It’s building muscle memory for when it counts.

The best don’t prepare until they get it right. They practice until they can’t get it wrong.

🤔 Ask yourself: Do you build deliberate practice into your team’s work?

Some people love the Patriots. Some hate them. Some don’t care.

But there’s no doubt they won. They did this by staying loyal—not to players or personalities—but to the system. Under Bill Belichick, they constantly reshaped the roster. Letting star players go. Letting fan favorites walk. Integrity of the mission mattered most of all, summed up in three words, “Do your job.”

Great teams aren’t loyal to the parts. They’re loyal to what the parts are there to build.

High-performing teams are built on loyalty—to each other, to the work, to the mission. But loyalty must be earned and aligned.

When someone stops pulling their weight—or when an old system or familiar process stops serving the mission—high-performing teams make the hard call.

High-performing teams are true to what matters most: the mission, the team, and the trust that binds them.

Loyalty strengthens the team—when it strengthens the mission.

🤔 Ask yourself: Is your loyalty strengthening your team—or slowing it down?

Trades have toolkits.

Carpenters have saws, chisels, and adzes. Plumbers have wrenches, spanners, and hammers.

Even specialists have specialized tools. Batman has a Batmobile, Batarang, and Batcomputer. Santa has a sleigh, sack, and magical reindeer.

So, what is a leader's toolkit? If you manage a team, run a function, or own a business outcome, what tools do you rely on?

Here are six core tools every leader should keep close.

#1. OKRs.

#2. Roadmap.

#3. Method.

#4. Management calendar.

#5. Backlog.

#6. Dashboard.

Your OKRs are your goals—a translation of strategy and mission for everyday use. The Roadmap is your build schedule: what you’re doing next, and when. The Backlog is your wishlist—team to-dos that flex in and around your Roadmap. The Method maps how work flows from input to outcome. A strong Management calendar defines the cadence and rhythm for work. And the Dashboard—prioritized, real-time KPIs that provide feedback and performance data for you and the team.

Let’s break each one down.

OKRs define what you’re aiming for.

You’ve set your mission. Your strategy. Now it must show up in your team’s work. Setting, testing, and running OKRs is the work of the team. It turns strategy into specific, actionable priorities.

They’re your focus and your filter—a signal of what matters most, and how you’ll measure success.

Run well, OKRs align effort across teams and avoid the trap of doing too much—or doing the wrong things well. They make goals concrete and force trade-offs. They’re the antidote to busywork.

If you’re prepping for a team offsite, kicking off a new quarter, or reviewing your roadmap, use OKRs to align priorities.

They center the team on what really matters, define success up front, and give you a shared scoreboard to spot success.

Watch out: too many goals, vague outcomes, or task-like key results turn OKRs into a glorified to-do-list.

💡 Pro tip: If your team hit all their OKRs last quarter, were they ambitious enough to drive real change?

The Roadmap lays out when and how you’ll get there.

A Roadmap is a plan. Think of it like a movie release schedule—what’s launching and when. You will spread the premieres over the year, and make sure your tentpole releases hit major holiday weekends. So it goes with your roadmap. You’ll pace the work, avoid overload, and time your biggest bets for maximum impact.

It’s a forecast—turning OKRs into time-based commitments the team can see, discuss, and deliver on.

Done well, your Roadmap is a visual answer to three questions:

What’s on the horizon?

What are we committed to?

How does it all connect?

Use it to set priorities over time—instead of reacting to whatever’s loudest today. This way, it’s both a planning tool and a communication device. It gives shape to strategy and shows the path ahead.

If you’re entering a new quarter, aligning across teams, or reviewing your backlog, use the Roadmap to sequence the work.

It connects the near-term to the big picture and keeps the team moving at the right pace.

Watch out: Roadmaps should force a choice. Those that try to please everyone become vague, bloated, and disconnected from what the team can actually deliver.

💡 Pro tip: If everything’s a priority on your Roadmap, it’s not a Roadmap—it’s a pressure cooker.

Method powers how you operate consistently.

Method is your team’s operating system—the repeatable rhythm that turns ideas into outcomes.

Methods differ by function.

In IT organizations, this might be Agile or DevOps. In Customer Service organizations, it could be case triage or tiered response. In Ops think lean or six sigma. In HR as a product, it would be the Flywheel. In Product or Innovation teams, it might be Design Thinking.

Whatever the method, it is the how of your business. The set of activities that build to create value, again and again.

Use it to define how work flows: How do ideas become initiatives? How do initiatives become results? A known process helps you spot bottlenecks, reinforce good habits, and build momentum.

The method is more than a process map—it’s a story of motion. It shows where you're building velocity, and where you're stuck.

If you’re scaling a team, improving delivery, or stuck in swirl—a method creates flow and focus.

It brings consistency to how you work and clarity to how you improve.

Watch out: when your method becomes dogma, it stops being useful. Tools should serve the team—not the other way around.

💡 Pro tip: Can your team describe your method in one sentence, and tell you where it breaks down?

A calendar provides the drumbeat of execution.

It’s your metronome—setting the rhythm for how and when your team makes decisions, checks in, reviews progress, and adjusts course.

What’s on your calendar? 1:1s. Team standups. Monthly staff. Retrospectives. Onsites or “development days.” Hackathons. Talent calibration. Backlog prioritization. Quarterly planning. Annual offsites.

It’s less of a to-do list and more of a production schedule. Miss a slot, and the whole line backs up.

Cadence creates predictability in a world of surprises. It embeds accountability through regular moments of focus and prevents swirl by making sure the right conversations happen at the right time.

Without cadence, everything feels urgent and ad hoc. Fire drills and late requests rule the calendar. With it, you create space to work on the business, not just in it.

If you’re planning a strategy offsite in April for June, it’s already too late.

Without a calendar set for the year, every planning cycle becomes a scramble of schedules, delays, and missed windows.

Watch out: cadence breaks when it’s reactive. If every meeting needs to be scheduled from scratch, you’re in fire-fighting mode.

💡 Pro tip: Can your team name the key rituals on your calendar—and say when the next one is?

A Backlog ensures nothing important gets lost.

It’s your source of truth for ideas, requests, bugs, and work that hasn’t been prioritized—yet. Use it to capture what matters without losing focus. Separate signal from noise—not everything on the backlog deserves action.

It clears the mental clutter of juggling short-term memory and the pile of Post-it notes, showing work isn’t forgotten, just staged.

Your backlog is a parking lot with a sorting system, not a junk drawer. It lets you say, “not now” without saying “never.”

Its most important role? It allows all work to be seen. Especially the kind that’s invisible or unspoken. Core work lives in your Method and Roadmap. Critical work shows up on the backlog and the calendar. Busy work should disappear. And secret work comes to light—and lands in the backlog.

If your team says, “We’re working on it,” but it’s not in the backlog, it’s not real.

If secret work keeps getting in the way of your OKRs, put it on the backlog.

The backlog is your accountability list. Not just for what you will do, but for what you have chosen not to.

Watch out: A backlog without discipline becomes a guilt trip. Pile on too much, or fail to prioritize, and it’s just another place where good work goes to die.

💡 Pro tip: What’s the oldest item on your Backlog—and what does its age tell you?

A Dashboard tells you if it’s all working.

It’s your real-time feedback loop: tracking progress, spotting red flags, and guiding action. It lives inside your management calendar and monitors OKRs, surfacing issues early and driving decisions.

Without a dashboard, you’re flying blind. With one, you’re course-correcting early and often.

But too many dashboards drown in data. Just because you can measure it, doesn’t mean you should. KPIs turn into MPIs—Many Performance Indicators. When everything is measured, nothing is clear—and no one acts.

Start with the decisions you want to make and the value you create. Work backwards. Don’t ask, “What can we measure?” Ask, “What do we need to know to act?”

Scrub for signal. What shows outcomes the business cares about? What’s just noise? If a metric doesn’t change behavior, ask if it belongs.

Show movement. Snapshots are vanity. Trends drive action. Set thresholds that force clarity. Red or green. Prune yellow.

Make ownership explicit. One person. Shared visibility isn’t shared accountability.

If you haven’t changed a decision based on your dashboard, you don’t have a dashboard—you have a scoreboard.

A good dashboard is simple. Sharp. A tool for decisions, not data.

Watch out: Dashboards without discipline become wallpaper. If it’s not actionable, it’s clutter.

💡 Pro tip: Can you draw a line from each KPI to decisions your team actually makes?

This isn’t just a toolkit, it’s a system for running your business—turning strategy into rhythm, motion, decisions, and results.

63% of product searches start on Amazon.

You know the drill. Type in “toe socks.” Click, filter, sort. You have options—sort by: Featured, Price (Low to High), Price (High to Low), Avg. Customer Review, Newest Arrivals, or Best Sellers.

Amazon knows something you don’t. If you are like most consumers, you won’t go beyond page one before you click and buy.

Amazon understands: prioritization is money.

In leading change, founder and former CEO Jeff Bezos said:

That durable business strategy—relentless efficiency, ruthless prioritization, and operational excellence—keeps Amazon ahead.

Bezos built Amazon around a simple truth: prioritize what won’t change. Customers will always want faster delivery, better selection, and lower prices. The way to sustain that? Cut friction. Eliminate waste. Move faster than the competition.

Efficiency, conversion, and speed are engineered into Amazon’s genes. Ruthless prioritization and efficiency are twin strands of its DNA.

Matt Garman, CEO of AWS, reinforces this:

“Operational excellence will build customer trust and a sustainable business.”

And it all starts with prioritization.

Click, filter, sort.

The same decision-making you use to buy socks—applied at a multi-million dollar scale. Amazon ranks, prioritizes, and executes with ruthless efficiency.

When you don’t prioritize—when you thumb down to page 37 without making a decision—you accumulate decision debt.

The draining dark side of poor prioritization.

Hesitation turns to missed opportunities. Missed opportunities turn into market failures. Failures turn into bankruptcies. Kodak. Blockbuster. Nokia. Sears. Failure to prioritize is a bankruptcy of focus—a slow death.

But don’t worry. You probably have a list of priorities.

Prioritization isn’t a list. It’s a strategy.

It’s a slow, creeping failure happening at every level—companies, functions, teams. Too many ideas. Too little capacity to execute. Work piles up, but fires, politics, and crises always jump the queue.

A lack of focus means friction takes over—burnout, chaos, or the squeakiest wheel.

Without intention, prioritization happens accidentally.

If this sounds familiar, here are six rules to help you focus, cut friction, and get real work done.

#1 Flow beats friction.

#2 Simple scales. Complexity kills.

#3 Constraints are fuel, not friction.

#4 Priorities are perishable. Refresh often.

#5 More work ≠ more progress.

#6 What gets done is what gets prioritized.

You’ve heard this before. If everything is a priority, nothing is. You must decide what truly moves the needle—for the team, for your organization or business—and cut the rest.

Except you won’t want to.

Without focus, work expands chaotically. Teams burn out chasing low-value work while the strategic, critical work suffers.

The graveyard of history is littered with companies that could not stop doing what they used to do. BlackBerry doubled down on keyboards, while Apple bet on touchscreens. In search, Yahoo spread wide while Google went deep. With AI, Google experimented, and OpenAI shipped.

Companies—particularly large ones—struggle with prioritization. The downside of scale means there are always more ideas than capacity.

Competing focus divides attention. And that shows up everywhere:

With all of these, the longer the list, the lower the throughput.

💡 Tip: Translate your strategy through OKRs and use them to ruthlessly prioritize and limit what you do.

Don’t be proud of complexity.

Complicated isn’t sophisticated. It’s just more chances for things to go wrong. More gears to gum up. The best operators know simplicity wins. They cut distractions, set clear rules, and remove unnecessary work.

But. I just need to add this piece.

Scope creeps—another meeting. Let’s add more options. Run this by someone else. Build science projects. Add more swimlanes. More alignment.

We try to please everyone and end up pleasing no one. Building for a rainy Tuesday with a blue moon takes a while. It bloats prioritization and stalls decision-making.

When we try to solve everything, we end up shipping nothing.

Simple scales, but only when it’s built in from the beginning. You can’t layer simplicity over a messy process. You have to design for it, then protect it.

That means:

Simple rules—especially boundary rules—create guardrails.

They help teams move faster by making it clear what’s in, what’s out, and what doesn’t need a meeting.

💡 Tip: Use OKRs to align teams around what matters. Then, remove anything that doesn’t move the needle.

You need more time, more money, more people.

You won’t get them.

You must work within limits—and make smarter trade-offs. That’s the job.

We treat constraints like a blocker. Something to work around. But they’re not the problem; they’re the point. They force decisions.

Avoiding decisions—delaying trade-offs, deferring calls, kicking the can—creates chaos later.

That’s decision debt. And the longer you avoid it, the more expensive it gets.

Some of the world’s best ideas come from working inside the box:

Constraints breed creativity. You may not name them, but they’re there:

Take time, for example. Most sales leaders will tell you, “time kills all deals.”

Marc Niemiec, CRO at Salesloft, turned that constraint into a rule.

“Deals that go quiet for 90 days don’t get a free ride. They either earn their place—with manager approval—or we give them a respectful exit from the pipeline. That’s how we keep things sharp.”

Using time as a constraint to force decisions resulted in cleaner forecasts, shorter pipeline meetings, more prospecting, and higher rep efficiency.

💡 Tip: A deferred decision is not free—it’s an IOU on future execution. Surface constraints early and let them shape smarter, faster trade-offs.

Priorities expire.

Strategic has a shelf life. Spin steals time. You set a plan, then something shifts. A customer churns. A new competitor pops up. A shiny object lands in your CEO’s inbox.

Recognize that the list of priorities is never static, but your job is to smooth that list—from frenetic to focused.

You need a way to absorb change and stay the course. To manage the day-to-day, filter out the fire-drills and drive to outcomes. Most teams strive to set priorities logically—tied to strategy and grounded in goals. But that’s not the full story.

Political reality pushes in front of strategy: Regulatory requirements, reputation control, and executive mandates. They don’t always align with the plan, but they shape the work.

You need structure and flexibility. A way to reset without unraveling.

Build a rhythm. Use OKRs as a forcing function—check weekly if the work still maps to outcomes. Then, quarterly, if the outcomes still make sense.

When political realities or fire drills push you off track, lean on simple rules. They help the team make faster decisions about what—and what not—to pay attention to.

💡 Tip: Bake in buffers. Even the most polished plan needs room to breathe.

More isn’t better. It’s just... more.

Teams often confuse motion with momentum. Jobs checked off, meetings held, backlogs grow. We multi-task. But nothing important moves.

When everything is in play, nothing finishes.

Pushing too much through the pipe creates a backlog of regret—a long list of projects you never have time for, wishlist items, and half-finished maybes.

This leads to unintentional, unconsidered prioritization. Instead of conscious choice, stress, overload, and burnout decide what is done and when. Every delay and re-decision adds drag.

Your goal isn’t volume. It’s throughput.

You don’t want more WIP; you want more finished work. And the quality, speed, and impact of that work improve when the system has some wiggle room.

Throughput improves when you limit what is in play, systematize repeatable decisions, and finish what you start.

That means making faster, better calls and turning recurring choices into routines. Routines reduce friction and give teams less time to get stuck in debate and more time to ship.

💡 Tip: Clear the WIP. Kill side-projects. Stop the busywork. Turn repeated decisions into routines.

Intent is nice, but execution is everything.

Your real priorities aren’t what’s on a whiteboard, a strategy deck, or shared in a town hall. They’re what you do. Where you spend your time. What ships. What gets in the hands of customers.

If it doesn’t show up in execution, it wasn’t a priority; it was a placeholder.

Leaders and operationally efficient teams don’t just list priorities; they make trade-offs, stop work, draw lines, and make hard calls.

If your team is asking, ‘What’s important?’—you aren’t leading; you’re listing.

The job then is to convert the commitment of a roadmap and the intent of a backlog into work. To pursue it relentlessly, make sure your team does too.

This is where prioritization becomes a discipline. You say no upstream, so execution can flow downstream. This clarity builds constraints. It drives execution, not discussion.

💡 Tip: Put every piece of work on the roadmap or the backlog. Root out secret projects. Prioritize both through your mission and your OKRs.

They float.

Words like empower, strategy, and culture hover in the air, detached from anything concrete. You say them, and the person you’re talking to looks up and to the right—a semantic search as they try to make meaning from the conversation. To make the abstract solid.

People do better when you make it real.

Instead of, “I empower you,” Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella is specific:

“Make it happen. You have full authority.”

One of the `floatiest, most detached, difficult-to-put-into-action words?

Ask five people what it means, and you’ll get five different answers—each preceded by a quick glance up and to the right. Responsibility? Ownership? Consequences? Leadership? Empowerment? The definition drifts from one vague word to another.

Split the word up. An account is what happened. Being able is having the power or skill to do something.

So, to be accountable is to make something happen.

Accountability is the A in RACI. You’re not Responsible (doing the work), Consulted, or Informed. But you are the one who owns the outcome—the one answerable for results, not just effort.

Taking accountability, in its simplest terms, is a shift from problem-reacting to outcome-creating.

Problem-reacting isn’t a great space to be in. It’s the confusing algebra of fire-fighting, short-termism, and tunnel vision.

Humans are natural problem solvers. We’re wired that way. We admire it professionally—doctors trained to diagnose symptoms, engineers who can break down complex systems, and entrepreneurs who identify challenges and turn them into opportunities.

But there’s a difference between solving problems and reacting to them.

When we slide down that slippery slope, we stop thinking expansively. We become rigid, defensive, and stuck. Stressed. We’re ruminative—we chew over the same issues again and again. Locked in the moment, treating symptoms instead of root causes.

We’re not accountable; we’re avoiding, blaming, making excuses. Or waiting, doubting, and complying.

Problem-reacting keeps us passive. Stuck. Powerless.

Outcome-creating is the better side of the equation—where energy fuels action, ideas take shape, and results happen.

In this space, we’re expansive. We’re bold, visionary, inclusive, and focused. We translate strategy, lift teams, and lead change.

When we’re outcome-creators, we are accountable. We own the outcome. We don’t wait for direction or permission—we step up, solve, and build.

We stay curious, agile, and in flow. We adapt, we improve, we learn. Rather than ruminate, we reflect—not stuck in what went wrong, but in how to get better.

Outcome-creating builds momentum. Focused. Resilient.

Taking accountability is like a math problem solved by simply moving the decimal point. We’re not shifting blame.

We’re shifting where you stand. You are the point.

Stand on the problem-reacting side of the equation, and everything happens to you. You’re passive, defensive, avoiding responsibility.

Shift to outcome-creating, and things happen because of you—taking ownership, driving action, and shaping results.

Small shift. Big difference.

Questions are the answer.

Taking accountability means thinking differently—and that starts with asking yourself the right questions. Hard questions. Questions that jump you out of the groove in your thinking.

It also means avoiding cliché answers—the comfortable responses that keep you stuck instead of moving forward.

Better questions create better outcomes.

Here are six questions to help yourself, and your teams, move from problem-reacting to outcome-creating.

#1. Where am I standing?

#2. What story am I telling myself?

#3. Am I inside the problem or above it?

#4. How do we move forward together?

#5. What’s the smallest step I can take?

#6. How do we make it stick?

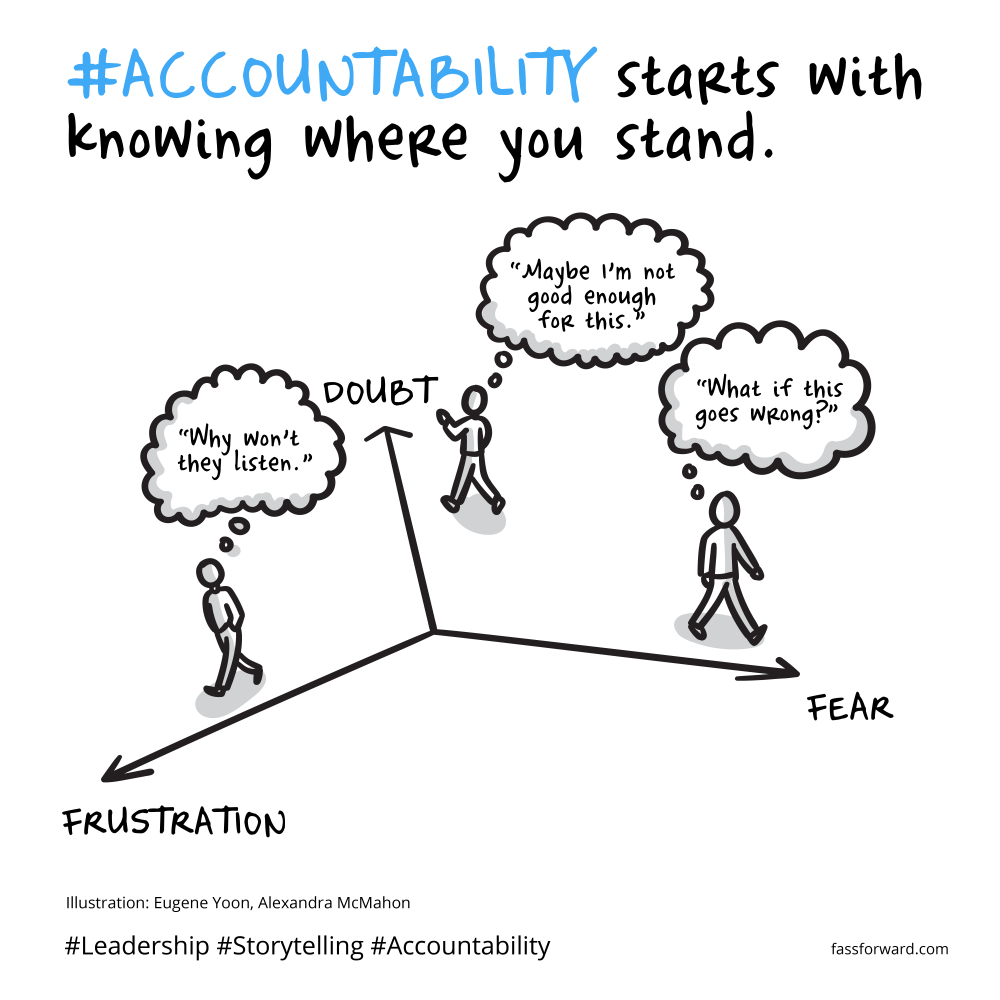

Accountability—moving the dot—starts with self-awareness. Before you can shift from problem-reacting to outcome-creating, you need to know where you are.

When you’re stuck in problem-reacting, you feel it. You wobble. You’re tense. Everything feels like a threat—to your security, control, or competence. Agitated, you take up defensive behaviors: blaming, avoiding, or waiting for someone else to act.

Spot the signs—nagging thoughts hold you back:

Security feels like fear. “What if this goes wrong?” → You avoid action.

Control feels like frustration. “Why won’t they listen?” → You push harder or shut down.

Competency feels like doubt. “Maybe I’m not good enough for this.” → You second-guess yourself.

Outcome-creators do something different. They recognize the trigger, take ownership, and shift the question. Instead of reacting, ask: