Open and explore more in ChatGPT

Imagine you were given $13,285,226 to invent something.

Better yet, you have sixty-two thousand customers ready to go. Evangelists. Early adopters.

So you take something good and make it better. You bolt on a USB charger. Add a waterproof Bluetooth speaker. Toss in an LED light. You take the idea of a Swiss Army Knife, smash it together with a cooler, and go nuts.

That was Ryan Grepper, the inventor of the Coolest Cooler.

In his words, “the COOLEST is a portable party disguised as a cooler, bringing blended drinks, music, and fun to any outdoor occasion.” Beyond the basics, his list of features was a grab-bag of tailgate dreams: A blender. A speaker. A phone charger. LED lights. A gear tie-down. Cutting board. Utensil storage. A bottle opener. All rolling on extra-wide tires.

It made a huge splash on Kickstarter and quickly became a huge failure.

Why do companies so often pursue innovation, and so often flunk?

I’ll bet innovation is somewhere in your list of priorities. Near the top of one of your strategy decks. Front and center at the next offsite. Snuggled between AI and customer obsession.

But while most large companies pin their hopes on innovation, only a handful of senior execs are satisfied with their performance, according to McKinsey.

So what’s going on?

While the well-worn Edison quote of “One percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration” is probably true, innovation doesn’t come from a single spark.

There is no Eureka! moment.

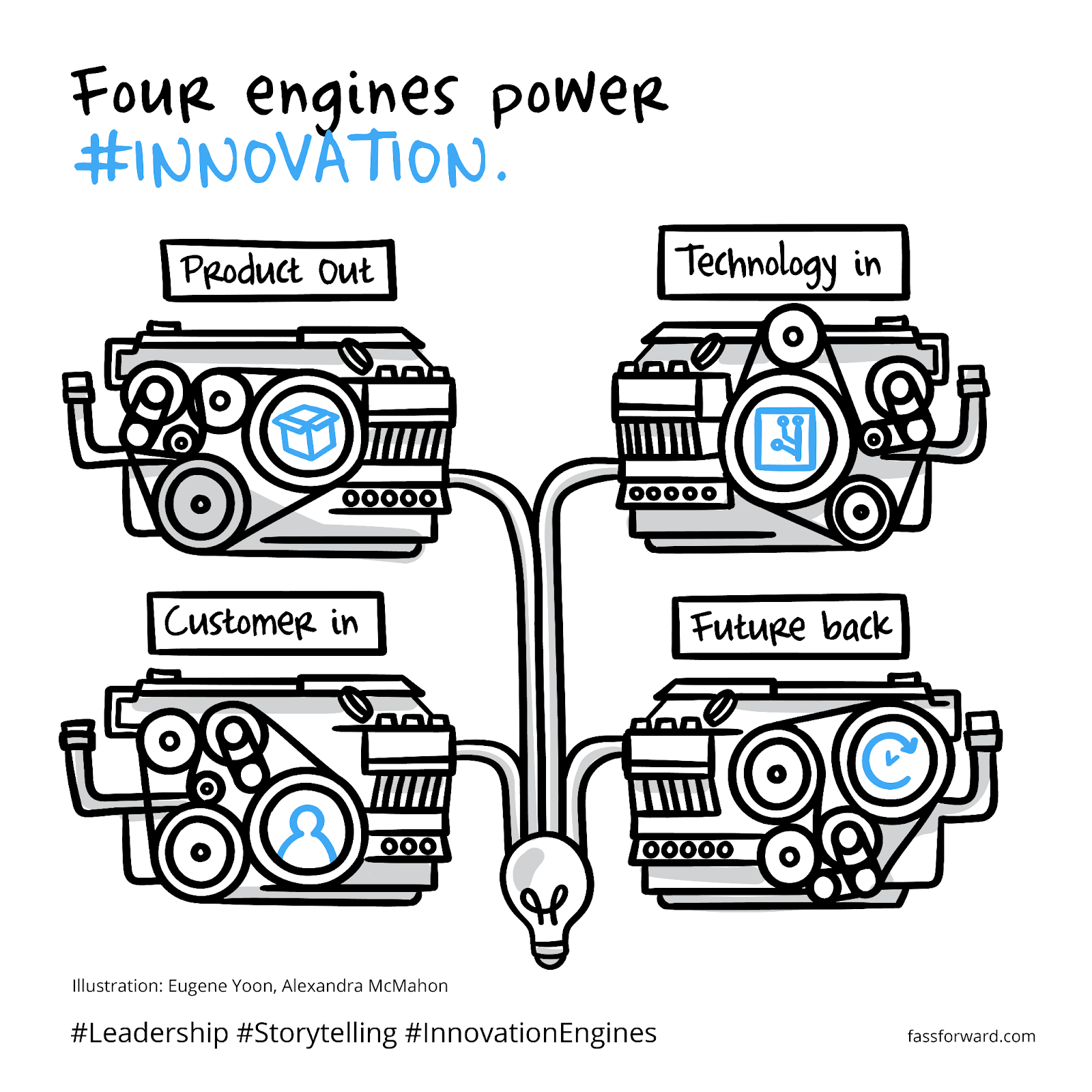

Innovation comes from running multiple engines concurrently. Each one pushing in a different direction, with a different mindset.

Innovative companies know this. These engines explain why innovative companies work—and where innovation fails.

Four engines power innovation:

Product out is about making the thing better.

Technology in borrows new tools, models, or technologies.

Customer in designs around customers' needs, not wants.

Future back bets on what’s next.

The out, in, and back are essential. They imply that each engine runs on a different track—a different vector. Each is a different point of view. Each requires a different mindset.

Product out is about engineering and iteration.

Technology in is about scanning and remixing.

Customer in requires empathy and observation.

Future back calls for vision and imagination.

Individuals, teams, and leaders are wired for one or two of those.

This is functional fixedness; if I have a hammer, everything is a nail. It’s the trap that makes us see a screwdriver and think it can only turn screws. We can’t imagine it as a lever, a wedge, or a weapon.

In organizations, this shows up as a disciplinary bias. Engineering teams run on Product out. Design teams and marketing live in Customer in. Technology naturally sees every problem as Technology in. Strategists and the senior team may bet on Future back.

To innovate, individuals and organizations have to be open to unlearning—ready to switch on, run, and align all of these engines.

Making the thing better.

This is the engine of iteration, refinement, and improvement. It’s feature-rich, tinkering, and fettling. It’s engineering-led, execution heavy, and often lives close to core operations.

This mindset comes with fixed phrases:

“Can we add a new feature?”

“How do we ship faster?”

“Let’s improve what we did last time.”

Real-world examples abound.

Think every iPhone generation from 1 to 15. Apple refines the camera, ups the display quality, and revs up the chip speed. Polish. Gain in increments. Each improvement drives share, sales, and margin, but the iPhone 15 isn’t fundamentally different from the first iPhone.

The same idea, kaizen’ed.

Most businesses live here.

Product out is the bread and butter of product development. It’s familiar. Comfortable. Budgeted. But Product out alone won’t give you breakthrough innovation. At best, it keeps you in the game. At worst, it’s a slow slide to irrelevance.

Overinvestment in product tweaks adds complexity, not value. It might be great engineering, but a poor market fit.

Borrowing new tools, models, or technologies.

This is the engine of adoption, adaptation, and remixing. It’s curiosity-driven. Outside-in. Often experimental.

It looks at what’s possible elsewhere—and asks, “What if we used it here?”

This mindset comes with fixed phrases:

“Can we plug this in?”

“What else could this do?”

“Who’s already solved a problem like this?”

Think touchscreen GPS. TomTom took map data, embedded systems, and touchscreen tech—none of it new—and combined it into a breakthrough consumer device. That’s invention as recombination.

The innovation wasn’t in the components—it was in the remix.

Technology in is scanning the horizon—and the competition—for something new to add to the mix. It’s the Estée Lauder chemist who goes to paint industry conferences to learn about advances in polymer science—and comes back ready to reinvent makeup.

It’s not just pure technology; it’s business model crossover; an Amazon team thinking about Airline loyalty programs, adding a pinch of Costco magic, and dreaming up Amazon Prime.

But Technology in alone is risky. Just because you can build it, doesn’t mean you should. Google Glass, anyone? Meta’s Smart Glasses? Segway?

That’s shiny object syndrome. Tool first thinking without a user point of view, a market that wants it, or an ecosystem ready for it.

Designing around needs, not wants.

Listening for the wish. This is the engine of insight, empathy, and behavior. It’s where design thinking sits. Understanding not just what customers say they want—but what they’re actually trying to do.

This stands product on its head.

Not, “here’s what we made.” But instead, “here’s what they need.”

This mindset comes with fixed phrases:

“Why are they doing it that way?”

“What’s the workaround here?”

“What’s the job to be done?”

Notion is a textbook example of innovation powered by the Customer in engine. They noticed people cobbling together ‘Frankenstacks’ of productivity tools. Notes in Evernote. Docs in Google. Tasks in Todoist. Then cobbling it together with Zapier and Slack. Notion built a product around how humans actually work, and innovated in the seams between software categories.

Airbnb, Venmo, and others understand that Customer in requires fieldwork: Ethnographic research. Usage data. Heat maps. Shadowing. User research before you build the product, not after, to validate all your hard work.

But Customer in alone isn’t enough.

Overindexing on the voice of the customer can lead to flops like New Coke and Heinz EZ Squirt ketchup. Both were short-lived consumer products where well-intentioned innovators only asked some of the right questions:

“Do you prefer your Coke a little sweeter?”

“Wouldn’t purple ketchup be fun?”

They got the answers they were looking for, not the behavior they were betting on.

What’s next? That’s a hard question to answer.

This is the engine of vision, foresight, and framing.

It’s strategy-driven. Narrative-heavy. Often uncomfortable. Scenario planning and long-bet thinking live here.

It starts with taking educated guesses at where the world is going—and asks, “How do we lead there?”

This mindset comes with its own fixed phrases:

“What’s the future we want to shape?”

“What will matter five years from now?”

“What’s the bold bet?”

Think of Space—building not just for the next launch, but to make life multiplanetary. Or Netflix—reading the bandwidth and pivoting to streaming while competitors clung to DVDs.

Future back is rarely obvious, except in hindsight. For every AWS and cloud, there is a Magic Leap and Second Life. It takes conviction, capital, and a tolerance for being early.

The engines run together and support each other.

One builds from the product.

One borrows from technology.

One listens to the customer.

One bets on the future.

Most teams run on one engine. Maybe two, if they’re lucky.

But the best innovations run on all four. They run in sync because the culture allows it, and the innovation story aligns with it.

OpenAI doesn’t just ship better models. That’s Product out.

It pulls in breakthroughs from transformer architectures and alignment research. That’s Technology in.

It shapes around human behavior—chat as the interface, natural language as the operating system. That’s Customer in.

And it’s betting big on what’s next. AGI. Safety. Multimodal reasoning. That’s Future back.

A culture that moves fast, tolerates ambiguity, and obsesses over mission.

And a story that frames the stakes—not just what they're building, but why it matters.

Culture makes it possible. Story makes it stick.

Open and explore more in ChatGPT!